|

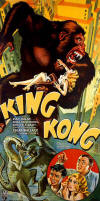

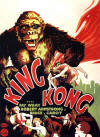

The chief distinctions of this famed monster picture

are conceded in the area of techniques―in the skill of manipulation of its

miniatures and trick photography—and

on the level of popular entertainment achieved with these mechanical effects;

but they are seldom considered sufficiently adult to assign it to the ranks of

the elite. King Kong is usually classed by highbrow critics among the lower

order of cinema freaks, or among the higher order of what they lightly term

kitsch or "camp." The chief distinctions of this famed monster picture

are conceded in the area of techniques―in the skill of manipulation of its

miniatures and trick photography—and

on the level of popular entertainment achieved with these mechanical effects;

but they are seldom considered sufficiently adult to assign it to the ranks of

the elite. King Kong is usually classed by highbrow critics among the lower

order of cinema freaks, or among the higher order of what they lightly term

kitsch or "camp."

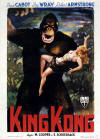

Yet, I find this fantastic fable of the capture of a giant primeval ape in an

anachronistic, prehistoric jungle and its removal to the alien environment of

New York City, where it breaks loose in a surge of love for a human female and

is finally destroyed atop the Empire State Building, to be a pictorial allegory

with implications more spacious and profound than had ever before been generated

in a mere monster or science-fiction film. It is a pure photographic phantasm in

which the range of the evolution of man from primate to urban cliff-dweller is

spanned in one imaginative conceit, and several ironies of social imbalance are

remarkably and morbidly symbolized.

I am sure that most of the millions who have seen and thrilled to this film

in its perennially popular circulations have not calculated what it is about

it that stirs their apprehensions and leaves them troubled and even

distressed. Most viewers simply see it as an uncommonly awesome and amusing

monster film. And I suspect that if they were confronted by the suggestion

that it seeds their minds with a series of subconsciously connective and disturbing images-images of the brutality and cruelty of

civilized man, of the enslavement of the

strong but ignorant masses, especially those of the Negro race; of the

frustration of sex in a society dominated by machines―they would laugh

at such an idea, as they laugh at much in the film—until they thought about it. Then they might see why I have picked this film.

King Kong is a prime example of a composite. It was compositely fabricated

entirely in a studio, with miniature animated models of prehistoric beasts,

including that of the monster hero, Kong, which was only eighteen inches high.

These models were animated and photographed on strips of film with blank

backgrounds, and these were superimposed on matching photographs of live human

action, fanciful paintings of jungle settings and such, to achieve the completed

picture. And it was a composite in concept, being a conscious combination of the

classic monster-picture plot with the currently expanding conventions of the

popular true-life travel-adventure films.

It follows closely the pattern of The Golem, first made in Germany in 1915,

which tells of a medieval statue into which a rabbi imparts life and which then

falls in love with a young woman, only to be repulsed by her. Driven mad by this

frustration, the creature goes berserk and plunges to death from a high tower. This is the basic pattern of most of the German monster films, which were made

during the 1920's, and the series of films about deformed humans and frustrated

freaks made by the ingenious Lon Chaney—The

Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), The Phantom of the Opera (1925), London After

Midnight (1927). Such films of fanciful occurrence were extremely popular. It follows closely the pattern of The Golem, first made in Germany in 1915,

which tells of a medieval statue into which a rabbi imparts life and which then

falls in love with a young woman, only to be repulsed by her. Driven mad by this

frustration, the creature goes berserk and plunges to death from a high tower. This is the basic pattern of most of the German monster films, which were made

during the 1920's, and the series of films about deformed humans and frustrated

freaks made by the ingenious Lon Chaney—The

Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), The Phantom of the Opera (1925), London After

Midnight (1927). Such films of fanciful occurrence were extremely popular.

But in King Kong, this formula was combined with the character and atmosphere of

the then increasingly

more popular travel and wildlife films. Indeed, Ernest Schoedsack and Merian C.

Cooper, who made King

Kong, had distinguished themselves originally with this type of

stranger-than-fiction film. Their Grass (1925) is a magnificent documentary of

migratory herdsmen in Persia, and their Chang (1927) is an excellent

documentary-fiction film that tells of a primitive family living in the jungle

of Siam. These films, along with such others as Robert Flaherty's Moana (1926),

W. S. van Dyke's Trader Horn (1931) and Frank Buck's Bring 'Em Back Alive

(1932), had served to acquaint the public with wild and exotic areas and

condition its abundant credulity for geographical and zoological caprice. Thus

the illusory power of the motion picture gave a certain plausibility to the

totally unscientific anthropological fantasy of King Kong.

An appeal to this power of illusion is made at the beginning of the film, with a

realistic simulation of a

travel film enterprise. An expedition is departing New York City for an

uncharted island in the Indian Ocean off Sumatra, where the expedition's

director has learned there is a fantastic collection of strange beasts. It is

his intention to make a motion picture of this mysterious place.

It is notable that Robert Armstrong, who plays Denham, the director, bears a

certain resemblance to Frank Buck and has much the same quality of a carnival

showman that Buck had. Also the fact that Denham picks up a beautiful, starving

girl off the streets of New York on the night before departure to go along and

play the heroine in his film had a similarity to the much-publicized episode of

W. S. van Dyke selecting an unknown, inexperienced female extra to take to

Africa to play the White Goddess in his location-made Trader Horn.

Schoedsack and Cooper have also continued to emphasize the real-life nature of

the expedition, with the motion-picture camera conspicuous on the deck of the

ship to make test shots and do rehearsals with the inexperienced girl, played by

Fay Wray. It is only as they approach the mystery island, known as Skull Island

because it has a mountain on it that looks like a skull, that they begin to

intrude the air of menace that was conventional in jungle films. Mists hang

around the island, great black birds hover over it and Max Steiner's monitory

music rumbles ominously. Schoedsack and Cooper have also continued to emphasize the real-life nature of

the expedition, with the motion-picture camera conspicuous on the deck of the

ship to make test shots and do rehearsals with the inexperienced girl, played by

Fay Wray. It is only as they approach the mystery island, known as Skull Island

because it has a mountain on it that looks like a skull, that they begin to

intrude the air of menace that was conventional in jungle films. Mists hang

around the island, great black birds hover over it and Max Steiner's monitory

music rumbles ominously.

The arriving expedition discovers one end of the island to be separated from the

vast interior by a great wall. It is on the other side of this wall, says

Denham, that the strange animals live. As the people from the ship approach the

near end, where the human inhabitants dwell, they hear the thumping of drums and

a weird chant rising from a thousand human throats, "Kong! Kong! Kong!" Then

they see through the trees the eerie glow of a strange, wild ceremonial taking

place. The natives, some dressed as gorillas, are dancing in a circle around an

altar to which a terrified native girl is lashed. When they spy the people from

the ship, and especially the white girl, Ann, they become greatly excited. They

want the "golden girl" to give as a sacrifice to Kong. Here is the first

suggestion of the appeasement of this mysterious beast, this creature that calls

up an image of the legendary minotaur, with the flesh of a human female. And the

further suggestion that the beast would be gratified with white flesh enhances

the erotic hint.

Of course, Denham and the ship's captain refuse the witch doctor and the native

chief when they demand that Ann be turned over to them. But that night the

natives kidnap her and take her back to the island, where they prepare her for

sacrifice. They tie her to a large stake and place this in the ground on the far

side of the wall; then they strike a huge gong to summon Kong from the interior

and line the top of the wall to watch.

Now, out of the twisted trees and giant vines rises the huge black shape of the

dreaded gorilla, with his great hideous face and shining eyes. Ann twists and

writhes in terror, but of course there is no hope, as the menace music thumps

like a heavy heartbeat and smoke from a hundred torches rises into the night.

With his eyes flashing anticipation, Kong deftly lifts Ann from the stake and,

clasping her to his vast chest, lumbers off into the jungle beyond the wall.

No sooner has this happened than a group of men from the ship arrive, led by

Jack, the mate, who has by

now become enamored of Ann. When they learn what has happened to her, they

boldly plunge into the jungle beyond the wall, hopefully going to her rescue—and

thus do we plunge from the initial period of comparative reality into the first

phase of pure fantasy. For here, in the depths of this strange jungle, the men

encounter giant beasts. "Something from the dinosaur family" is brought down

with a gas bomb. While crossing a lake on a makeshift raft, they are attacked by

a giant water monster.

On ahead, Kong, with Ann in his giant paw, comes upon one of the men on a log

bridge. Very gently, Kong sets the girl on the ground, heroically thumps his

chest a few times, then grandly destroys bridge and man. Ann escapes, but Kong

rushes to her when he hears her screams and rescues her from a huge lizard in a

marvelous prehistoric wrestling match. Kong wins, of course. He ends the battle

by ripping the lizard's jaws apart, then tries, in his mute way, to show Ann

that he is very fond of her—with

the mood music slyly helping him. On ahead, Kong, with Ann in his giant paw, comes upon one of the men on a log

bridge. Very gently, Kong sets the girl on the ground, heroically thumps his

chest a few times, then grandly destroys bridge and man. Ann escapes, but Kong

rushes to her when he hears her screams and rescues her from a huge lizard in a

marvelous prehistoric wrestling match. Kong wins, of course. He ends the battle

by ripping the lizard's jaws apart, then tries, in his mute way, to show Ann

that he is very fond of her—with

the mood music slyly helping him.

Later on, there's another thrashing battle between Kong and a huge water snake,

and yet another with a giant pterodactyl on a mountain ledge. But while this

struggle is raging, Jack arrives and makes off with Ann, a perilous maneuver

which Kong tries in vain to prevent.

Meanwhile, back at the wall, the scattered crewmen have reassembled and are

wondering what to do, when Ann and Jack emerge from the jungle, with Kong

crashing through not far behind. The giant ape, fired with passion, pushes down

the gate, scatters the terror-stricken natives and goes after the whites, who

are trying to escape in a boat. As a last delaying maneuver, they fling a gas

bomb at the ape and, sure enough, it stops him. He falls anesthetized in his

tracks! Now Denham realizes what a treasure they can have by lashing Kong in

chains and taking him back to America. "We're millionaires, boys!" he exults.

"I'll share it with all of you! We'll have his name up in lights on Broadway: Kong, the Eighth Wonder of the World."

Dissolve now to the inside of a theater. Denham comes out on the stage to

introduce the show. "We

have brought back the living proof of our adventure," he says. The curtains open

and there on a platform is

the heavily shackled Kong, and on the stage beside the platform stands Ann in an

evening gown. "Look at

Kong," shouts Denham. "He was a god in his world!" The great ape wrenches at his

shackles. "There the beast and here the beauty!"

Then Jack is brought on in dinner jacket to pose with Ann for photographers and

to announce the romantic culmination of the expedition. But Kong, seeing him, is

infuriated with jealousy and hate. Further, the surprise of the photographers'

flashes causes him to leap with fear. With a great crash and rending, Kong pulls

free from his chains. The audience flees in panic. Kong breaks through the wall

of the theater and terrifies pedestrians and motorists as he bursts into the

street. Making straight for the building into which Jack has fled with Ann, he

scales the outside of it, shoves his huge arm through the window of the room in

which the two are fearfully cringing, grabs Ann in his giant paw and departs

with her over the rooftop and then down the outside of the building to the

street below. Still clasping his precious handful, he rips up the elevated

tracks and looms in front of an oncoming train which crashes calamitously

through the gap he has made.

The city is in an uproar. Police are calling for help. Now a flash goes out over

the radio: "Kong is climbing

the Empire State Building!" And, in a splendid distance shot we see the creature—superimposed,

of course—climbing

up the outside of the familiar pylon-topped skyscraper. The city is in an uproar. Police are calling for help. Now a flash goes out over

the radio: "Kong is climbing

the Empire State Building!" And, in a splendid distance shot we see the creature—superimposed,

of course—climbing

up the outside of the familiar pylon-topped skyscraper.

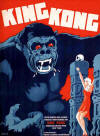

Perched on the top of the pylon, with Ann clasped in his hairy paw, Kong is the

symbolization of the gross power of primitive, emerging man. Then modern man—civilization—calls

forth the ultimate weapon to bring him down-airplanes—and

in a moment, a swarm of them converges on the tower. As they near Kong and start

firing at him with machine guns, he gently places Ann on a narrow ledge, and,

with his arm thus free, lashes wrathfully at the planes which seem like tiny

gadflies as they swoop past. He catches one plane that ventures too close and

flings it, crumpled, to the street far below. But it is in vain. He is hit again

and again by screaming bullets. He picks up Ann for a last loving, tender-eyed

caress—all

he has ever been able to show her—while

she cringes in horror, then places her back on the ledge.

Now the great brute wobbles. His hideous face shows crinkled agony. Then he lets

go of the pylon and

plunges at last to the ground. On the street below, policemen and reporters are

gathered around Denham. "Well," says one, "the airplanes got him." And Denham

sadly and solemnly replies with what is clearly a

howling understatement, "Oh, no, 'twas beauty killed the beast."

No matter how used to the illusions of motion pictures one may be, there is an

irresistible excitement to

be got from this fanciful film, outside of the wildly imaginative tale it spins.

Perhaps the freakish power of its suggestion pricks some depth of atavistic

fear, touches some subconscious stratum of primitive animal dread. Kong is more

physically substantial and therefore less difficult to believe than the monsters

evolved out of statues or the gruesome specimens of human deformity. And since

he is a manifest of nature, he becomes an affecting metaphor just as do all

folk-tale animals when they are presented as symbolizations of humankind.

Remember, King Kong was initially released in March 1933, at the depth of the

Great Depression, when millions

were out of work and a sense of inhuman betrayal

by the social system was surging through the

land. Though critics and audiences did not bail it as an allegory of the times,

nor did Kong leap forth as a

symbol of the helpless working man, there was obviously some strange empathy

felt toward this cruelly

badgered beast by millions of unemployed who saw the picture in 1933.

Likewise there is inducement for subconsciously sensing Kong as a massive

symbolization of the segregated Negro race. Kong is black. He is taken from the

jungle and transported to America in chains. Here he is used to serve a white

master who exploits him unmercifully. Likewise there is inducement for subconsciously sensing Kong as a massive

symbolization of the segregated Negro race. Kong is black. He is taken from the

jungle and transported to America in chains. Here he is used to serve a white

master who exploits him unmercifully.

But most suggestive and pervasive in the picture is the theme of frustrated sex,

which is superficially

funny but essentially sad and ominous. An irony (undoubtedly unintended) is that

poor old Kong finally

retreats to the top of the Empire State Building, which is—or

was, until its peak was adorned with spiky television antennae—the

most elaborate phallic symbol in the world.

King Kong was immensely popular. It is the only film that ever played the Radio

City Music Hall and the Roxy Theater in New York simultaneously. The figure of Kong became synonymous

with the concept of

superhuman strength and quickly merged into the folklore of our mechanical age. |